Understanding Typical Memory Changes with Age

Aging is a natural part of life, and with it comes a series of physiological and cognitive changes. Among the most widely discussed—and often feared—are changes in memory. As people age, it’s common to notice subtle shifts in memory performance: forgetting names momentarily, misplacing items more frequently, or needing longer to learn new things. These experiences are often brushed off as “senior moments,” but they can lead to anxiety about cognitive decline or even dementia. However, not all memory lapses are signs of a serious problem. Understanding what constitutes normal age-related memory changes and how to distinguish them from pathological memory loss is essential for individuals, caregivers, and healthcare professionals alike.

This article will explore the science behind typical memory changes with age, their causes, how they differ from dementia, and what strategies can be employed to support healthy cognitive function throughout the aging process.

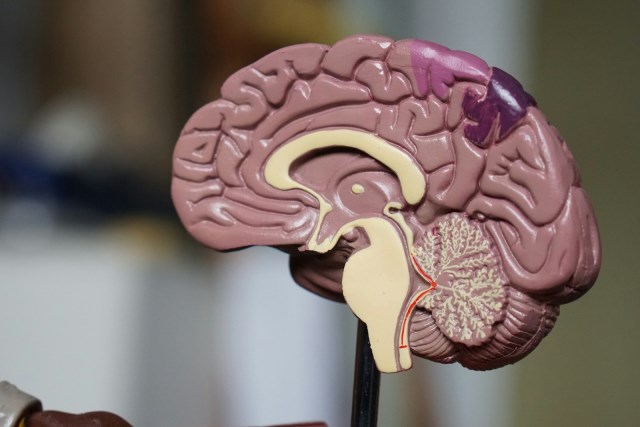

The Structure of Memory: A Quick Primer

Before diving into how aging affects memory, it’s important to understand what memory is and how it functions. Memory is not a single process but a collection of systems that encode, store, and retrieve information. These systems are generally divided into three main types:

- Sensory Memory – Briefly holds sensory information (a few seconds or less).

- Short-Term (Working) Memory – Maintains and manipulates information over a short duration (about 15–30 seconds).

- Long-Term Memory – Stores information over extended periods. This includes:

- Episodic Memory (personal experiences)

- Semantic Memory (general knowledge)

- Procedural Memory (skills and tasks)

Different areas of the brain are involved in processing these types of memory. The hippocampus and prefrontal cortex, for instance, play critical roles in forming and recalling episodic memories—areas especially sensitive to age-related changes.

What Are Normal Age-Related Memory Changes?

Normal aging does affect memory, but not all memory functions decline equally. Here are some typical, non-pathological memory changes commonly observed in aging adults:

1. Slower Recall

Older adults may take longer to retrieve information. For instance, recalling a familiar name might not happen immediately, but it usually comes to mind later.

2. Reduced Working Memory

Tasks that require holding and manipulating information—like doing mental math or following complex instructions—can become more challenging.

3. Decline in Episodic Memory

People might forget details of recent events or conversations, but can usually recall them with prompting. Memories from years ago remain largely intact.

4. Naming Difficulties

Tip-of-the-tongue experiences become more frequent. While frustrating, they are not uncommon or alarming unless persistent and worsening.

5. Slower Learning

Acquiring new information or skills takes more time and repetition compared to younger individuals.

These changes are usually mild and do not significantly impair daily functioning. Importantly, they differ from the more profound memory deficits seen in neurodegenerative diseases.

Causes Behind Age-Related Memory Changes

Several biological and psychological factors contribute to memory changes with age:

1. Brain Structure and Function

- Hippocampal Shrinkage: The hippocampus, vital for memory consolidation, tends to shrink with age.

- Prefrontal Cortex Decline: This region governs attention and executive function, and its degradation can affect memory organization and retrieval.

- Reduced Neuroplasticity: Aging brains generate fewer new neurons and connections, impacting the ability to adapt and learn.

2. Slower Neural Processing

Cognitive processing speed declines with age. This slower pace can hinder the brain’s ability to efficiently encode and retrieve memories.

3. Reduced Blood Flow

As vascular health declines, reduced cerebral blood flow may lead to diminished cognitive performance, including memory.

4. Changes in Neurotransmitters

Levels of neurotransmitters like dopamine, acetylcholine, and serotonin decrease with age, affecting mood, attention, and memory.

5. Sleep Disturbances

Poor sleep—common in older adults—can significantly impair memory consolidation.

6. Stress and Depression

Chronic stress elevates cortisol levels, which can damage the hippocampus. Depression, common among seniors, is also associated with memory difficulties.

Differentiating Normal Aging from Dementia

It’s crucial to distinguish between typical memory lapses and more serious cognitive decline, such as dementia. Here are key differences:

| Normal Aging | Possible Dementia |

|---|---|

| Occasionally forgetting names or appointments | Frequently forgetting recent events or repeating questions |

| Misplacing things but retracing steps to find them | Placing items in unusual places (e.g., wallet in the fridge) |

| Slower recall of information | Inability to recall information even with cues |

| Occasional word-finding difficulties | Substantial language problems or confused speech |

| Occasional poor judgment | Poor decision-making and inability to manage finances or medication |

Memory decline that disrupts daily life, affects independence, or worsens over time should prompt evaluation by a healthcare provider.

When to Seek Professional Help

Some signs warrant professional assessment:

- Consistent memory problems affecting work or social life

- Getting lost in familiar places

- Confusion about time or place

- Difficulty with familiar tasks (e.g., cooking, paying bills)

- Noticeable changes in personality or behavior

Early diagnosis is vital, especially for conditions like Alzheimer’s disease or vascular dementia, where interventions can slow progression.

Enhancing and Protecting Memory in Older Adults

Although some memory decline is inevitable, there are ways to support brain health and mitigate its effects.

1. Mental Stimulation

Engaging in intellectually challenging activities like puzzles, reading, learning new languages, or playing instruments can help maintain cognitive function.

2. Physical Exercise

Regular aerobic activity improves blood flow to the brain and supports the growth of new neurons. Walking, swimming, and yoga are particularly beneficial.

3. Healthy Diet

A brain-healthy diet includes:

- Omega-3 fatty acids (e.g., salmon, flaxseed)

- Antioxidant-rich fruits and vegetables

- Whole grains and legumes

- Low sugar and salt intake

The Mediterranean diet is frequently recommended for brain health.

4. Social Engagement

Staying socially active reduces the risk of cognitive decline. Interacting with friends, volunteering, or joining community groups fosters mental stimulation and emotional well-being.

5. Sleep Hygiene

Improving sleep through a regular schedule, limiting caffeine and screen time, and creating a calm sleep environment is crucial for memory consolidation.

6. Stress Management

Practices like meditation, deep breathing, and mindfulness can reduce cortisol levels and protect the hippocampus.

7. Routine and Organization

Using planners, alarms, and consistent routines can compensate for memory lapses. Keeping a designated spot for essentials like keys or glasses is also helpful.

Technology and Tools to Support Memory

Modern technology can assist older adults in managing memory issues:

- Smartphones and Smartwatches: Reminders, calendars, and voice assistants can help with tasks and appointments.

- Medication Management Apps: Tools like Medisafe offer pill reminders and tracking.

- Voice Assistants (Alexa, Siri): Useful for setting reminders and retrieving information.

- Memory Games and Brain-Training Apps: Programs like Lumosity and Peak offer cognitive exercises tailored for older users.

These tools offer both convenience and peace of mind for aging individuals and their caregivers.

Cognitive Reserve: Building a Resilient Brain

The concept of cognitive reserve suggests that individuals with higher levels of education, complex occupations, and lifelong learning can better cope with age-related brain changes. Essentially, they build a “buffer” against decline.

Ways to build cognitive reserve:

- Pursue lifelong learning and continuing education

- Read widely and regularly

- Engage in problem-solving and analytical tasks

- Cultivate hobbies that challenge the brain

Even in older age, it’s never too late to start building cognitive reserve.

Myth-Busting: Common Misconceptions About Aging and Memory

Myth 1: Memory loss is inevitable and always means Alzheimer’s.

Fact: While some decline is normal, severe memory loss is not. Many older adults maintain sharp minds well into their 80s and 90s.

Myth 2: Brain function can’t be improved in old age.

Fact: Neuroplasticity exists throughout life. The brain can form new connections and adapt, even in later years.

Myth 3: You should worry about every memory lapse.

Fact: Occasional forgetfulness is normal and not necessarily a sign of disease.

Myth 4: Mental decline is only genetic.

Fact: Lifestyle factors—diet, exercise, learning, and socialization—play a significant role in cognitive aging.

Looking Forward: Aging with Confidence

Understanding what constitutes typical memory changes with age can empower individuals and their families to respond with informed action rather than fear. While aging brings cognitive shifts, it also offers opportunities to focus on wellness, adapt habits, and leverage tools that support memory function.

By emphasizing prevention, encouraging healthy lifestyle choices, and using supportive technologies, people can maintain cognitive vitality for many years. The key lies in recognizing the difference between what is normal and what is not, and in fostering a proactive rather than reactive approach to brain health.

In conclusion, aging does not necessarily equate to significant memory loss. With awareness, preparation, and ongoing mental and physical engagement, older adults can continue to lead fulfilling, intellectually rich lives well into their later years.

Photo by Robina Weermeijer on Unsplash